Paola Miglio

Lima, Peru

El Trinche; World’s 50 Best Restaurants – Academy Chair for South America (North)

Instagram: @paola.miglio @eltrinchecom

*Changemakers is a Cross Cultures series spotlighting inspiring women who are creating and doing in the F&B ecosystem; eading the way and helping better the world.

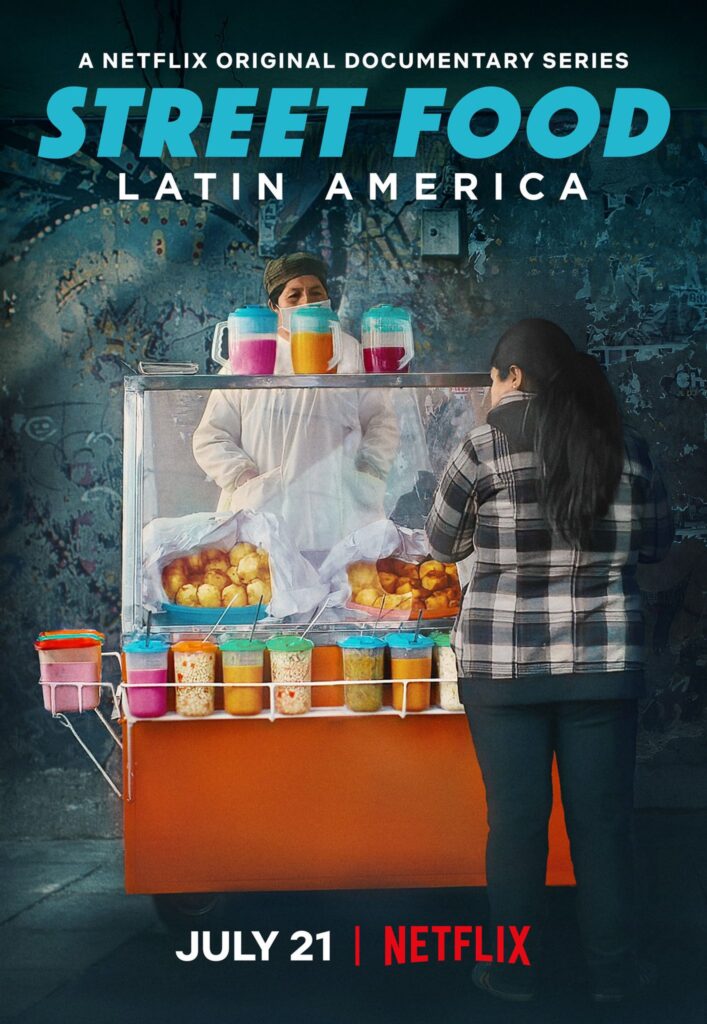

Born and raised in Lima, Peru, Paola Miglio is editor in chief at El Trinche, a food and travel website, as well as the World’s 50 Best Academy Chair for South America (North). She was the talent advisor and researcher for the recently released Netflix “Street Food: Latin America” Lima episode, and she co-wrote and co-edited the book, Perú, El Gusto es Nuestro, which chronicles the last 12 years of history of Peruvian gastronomy.

In 2002, Paola moved to Madrid and traveled for a period of five years—wanting to do anything but journalism. But after the 2004 train bombings in the Atocha station—one block from her home—she realized that, having lived through the biggest crisis and terrorism war in Lima, during Alberto Fujimori’s dictatorship—nobody is safe anywhere. So in 2006, she decided to move from her comfort zone and return home.

In the light of COVID-19, she and her team at El Trinche started a guide to connect the little bodegas, producers and sellers with people—creating a huge network calling for readers to tip them about places that sell groceries in their neighborhood. It was shared more than 200,000 times on social media. They also started an IG Live series called “Antilives,” speaking with chefs like Virgilo Martinez and Pia Leon in Lima, and Diego Oka in Miami, where they shared practical tips that may help during this period and new ways of doing business in the world of gastronomy.

Tell us about you. Where were you born, raised, and what you are making or doing at present?

I was born and raised in Lima, Peru. Now I’m editor in chief at El Trinche, a website about food and travel, also freelance writer and book editor, and the 50 Best Academy Chair for South America- North.

How did you end up working at your present career? How long have you been doing this/ When did you start?

I studied Linguistics and Literature at de Catholic University in Lima (Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú), and started to work in a local paper when I was 19 years old (1995-6), at the cultural section. I used to write about art, cinema, books. Then I was trained in the local section, reporting the city facts (strikes, city events, the day to day journalism). After that I started in the Sunday magazine (at the same journal) with special reports about the city and long chronicles. My editor gave me the food section at the same time and I started to write about food and chefs. The food movement was not that intense at that time. After five years I move to another paper, and magazines like Caretas, Oiga, Etecé, worked as a freelance for El Comercio and then I decided to move to Madrid to do anything but journalism. I traveled around for 5 years and then went to Oslo University and took up a short Media Studies Course. Then I came back and the gastronomy boom was already happening in Peru. I started to work for some magazines, like El Gourmet and Sommelier, for El Comercio and editing a music magazine for 4 years, among other curious publications. Then everything was like a snow ball. In 2008, I started to write more about food and chefs and was the editor of the City Section of a Political Magazine called Velaverde. Then I was called for El Trinche Project and to write about food for La República, and finally I ended running El Trinche, having a column about restaurant critic at El Comercio (closed because the pandemic) and co-writing and co-editing the book Perú, El Gusto es Nuestro, the history of the last 12 years of Peruvian gastronomy.

What was the biggest challenge you have faced?

Personal. Moving to Madrid to start to work in whatever, I choose not to do journalism. I had already a career in Lima, and nobody knew me in Madrid. That was hard, not devastating, but hard. Missing, not been able to see my people. We didn’t have social media or smartphones to speak every day. But I was getting comfortable with the years, with no plans of coming back, planning to move to London with some friends. Then, one day, the Atocha bomb exploded, one block away from my house in Madrid. That was quite scary after living during the biggest crisis and a terrorism war in Lima (20 years) and Alberto Fujimori’s dictatorship; target a lot of fears and insecurities. It made me realize that nobody can be completely safe anywhere. I decided to stop traveling abroad for a while and start traveling in my country, which was more complicated and difficult because of the distance and connections (because of the terrorism a lot of places in Peru, we not able to visit during a lot of years). It was time to move from my comfort zone again.

Work. I don’t think that I had a “biggest challenge” in my work life but a lot of little challenges that were fun (sometimes not that fun) to overcome. I consider myself quite privileged in the work I choose to do. I like it. I enjoy it. Sometime I think I do not have the right to complain. I worked hard to achieve every step, but that is what you suppose to do, isn’t it? Do not waste the opportunities and work hard to demonstrate that you can do it, especially if you are given the tools to do it. It is a responsibility. As a woman, I experience some rejections and less pay, mansplaining when I started to travel alone (when I came back to live in Lima I did it a lot as a researcher for a travel guide collection), and years later, when doing restaurant critic. That always affects you. You don’t realize how much until you process it and start think about it properly.

How/ what did you do to get over it?

I just had to learn how to speak up. My generation in Peru was raised in a war and in a very machista society, even some of the most opened, progressive and liberal minds, have some machismo incorporated. Men and women. I had to overcome my machistas ideas and became a proud feminist. I’m still working on that, it’s not easy. My cousins and friends helped. It is a challenge day by day: not only in Peru but also in the “developed” countries, were many people think that there is no machismo involved in the kitchen or in their lives.

What is the best advice you can give to anyone wanting to get into or excel in your field?

Read, eat, travel. Go to seminars and workshops to refresh your writing, pay some of your trips, pay also for some of your food, tip. Tip. Go to the field, talk to the producers, bond, get dirty, get wet. Harvest. Connect, listen and try to empathize with their worlds: there are not better or worst just different. We are not always going to be right, we don’t know all, we learn in the journey. Ask, even the questions you know are going to be awkward, you are a journalist, not Miss Simpatía, your job is to ask. We are not PRs. Do not sell your opinions. And definitely, you have to understand that you are not the principal character of the stories you are writing. Be humble and stop collecting Instagram photos with chefs: those do not make you a better journalist.

What is your favorite thing about your culture or living in your city?

The Ocean, the food, my people. You can eat well almost everywhere. The ability to overcome extreme situations with creativity. Drink leche de tigre and beer in a sunny morning with friends cures everything. The gray sky in a winter morning: that’s the smell of Lima.

How did you spend your days during this COVID-19 quarantine period?

At home, after a few years traveling non-stop, I had to stop. It was a shock at the start, we thought it was a phase, but no. Peru was the first country, I think, in Latin America that closed borders and where everything was on lockdown, even restaurants and delivery. But it was not enough. Everyone can see it now. We are still in a difficult situation. After 3 months, restaurants started with the delivery and one week ago they start to open. I’m still at home, there is not an obligatory lockdown in Lima, but if you can, the government recommends to stay home. It’s not an easy situation and the next 3 weeks are going to be hard. Of course, as many colleagues and people, I’ve lost jobs, but we should focus on working more and reconnect with the basics.

At the beginning of the pandemic, as there was no delivery and the supermarkets and markets crowded (the cues were endless) we started in El Trinche a guide to connect the little bodegas, producers and sellers with the people, calling by phone, making a huge network of people that called to tip us about places that sells groceries in their neighborhood (a lot of little markets here disappear during the years because of the huge supermarkets that are in every corner). I think it helped a little, because was shared more than 200,000 times in social media. Now, in this new phase, we are trying to show the restaurants and their offers. I think it is not time to criticize; our industry is devastated and trying very hard to rise, to follow all the protocols. We have to show some respect for their effort. Of course, we are not being patronizing, we recognize some flaws and if they affect the integrity or health of someone we comment on them, but the small ones, those amending ones, are solved step by step. The criticism now is more focused in structural problems, to rebuild in a good way; in sustainability, biodiversity, well paid jobs, equality, nutrition, agriculture, vendors chains, OMV.

Please tell us about your work at Netflix’s “Street Food: Latin America – Lima”.

In the Lima chapter I helped as a talent advisor and researcher. I was behind the scenes, I liked that way (when the filmed the Lima Chapter I was in a work trip). I got in touch with many of the street food vendors, talked with them hours, and beyond the chapter, it was very fulfilling to know them closely and visit their homes, share with them and keep in touch during difficult times. Many of them are opening again, I’m very glad to hear them telling about their new plans.

Please tell us about the IG Live sessions you have been hosting with El Trinche with Peruvian chefs, especially during this COVID-19 period.

We focused on doing deep interviews (written) and started talking about the real problems in the kitchen. It was not easy to see the chefs’ vulnerability, the showed up as they are. The IG lives were the way to communicate and talk about the different industries that are part of the gastronomy. We called them “Antilives,” we decided to talk about practical stuff, that may help during the period, and show examples of re-openings but also new ways of doing business in gastronomy.